Remembering African Gunners of World War 2

East and West African Artillery

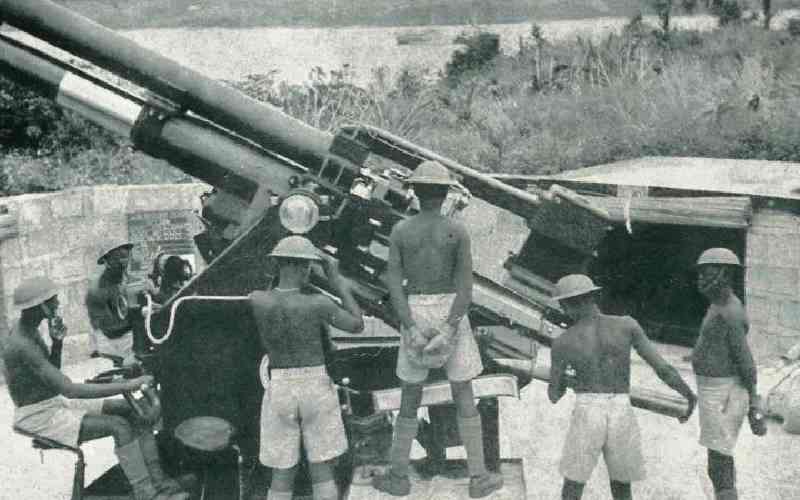

Tens of thousands of African soldiers served with British forces during World War Two. Of these, several thousand served with the artillery. African artillery units defended African ports, airfields and lines of communication of strategic importance to the Allied war effort. Some took part in the conquest of Italian East Africa and the liberation of Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Several units served overseas: in the occupation of Madagascar; the defence of Ceylon; and against the Japanese in Burma. From a starting point of near zero in 1939, numerous artillery regiments and batteries of all types were formed, equipped and trained - reaching a peak in 1943-1944.

In 1939, the British colonies in East and West Africa were each defended by a small infantry force. Strategic ports were defended by a few pieces of obsolete coastal defence artillery. The war seemed far away and to be largely a European affair. Following the dramatic events of May and June 1940, the war suddenly moved to the very frontiers of East and West African territory. In East Africa, the threat came from the Italian-occupied Ethiopia (Abyssinia) and Italian East Africa, most notably from the Italian air force. In West Africa, the one-time friendly neighbouring territories of French West Africa now became potentially hostile under the government of Vichy France. Although direct attack from Vichy forces was a possibility, the more significant fear was of German and Italian forces using French territories to attack their British neighbours. The British, under aerial bombardment, threatened by the invasion of their homeland and struggling to replace losses after Dunkirk, could spare few men to defend vital assets in East and West Africa.

The expansion of East and West African forces now began in earnest. African soldiers were recruited in large numbers, forming mixed units with British Officers and N.C.O.s. It appears that tribal chiefs and local rulers played an important part in encouraging their young men to enlist.

A campaign was begun to evict the Italians from Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea and involved not only African troops but those of Britain, India and South Africa. The concentration of South African troops in Kenya, arriving at the port of Mombasa was protected from aerial attack by South African anti-aircraft units. The successful campaign which followed involved field artillery of the British, Indian and South African armies. It was the entry of Japan into the war in December 1941 that gave real impetus for the development of the East African Artillery. Mombasa and the sea lanes passing up and down the East African coast were now to be defended against naval attack and from attack by ship-borne aircraft. British anti-aircraft units were sent out to form the nucleus around which a new, East African anti-aircraft force could be built. Later, field artillery units were raised for the 11th (East African) Infantry Division which went to Ceylon and then Burma. A heavy anti-aircraft regiment was also sent to Burma.

In West Africa, Freetown on the coast of Sierra Leone was an essential refuelling stop for ships carrying British reinforcements to the Middle East, India and the Far East. With the air reinforcement route over France having been closed, an alternative route was needed by which British and, later, American aircraft might land and refuel on their way to the Middle East. The Takoradi air route, from West Africa to the Sudan, was developed to address this need. Local African men were recruited and trained by British cadres despatched form the United Kingdom. As in East Africa, the priority was for anti-aircraft and coast defence artillery. With the British and Commonwealth success in the Western Desert and the Allied invasion of North Africa, the Axis threat to West Africa disappeared. Two infantry divisions were prepared which would join British and Indian troops in Burma – field artillery regiments were raised as part of these divisions. Anti-aircraft artillery was re-purposed and a brigade of three regiments of heavy anti-aircraft artillery (later supplemented by a fourth regiment) was also sent to India, freeing up British and Indian units to accompany the 14th Army on its reconquest of Burma. The arrival of the African anti-aircraft regiments helped to release British counterparts for disbandment to provide sorely need reinforcements for the British infantry.

As can be seen from this brief outline, African gunners made a significant contribution to the Allied war effort. Prior to enlistment, many were poorly educated and had few if any skills in operating modern vehicles and equipment. Subsequent military experience gave the men an education and trained them in many things mechanical and organisational. Those deployed overseas were exposed to new cultures and new ideas. There was mutual prejudice between the African gunners and their European Officers and N.C.O.s – both of a racial and class hierarchical nature – but little if any outright hatred. The closer the men came to the fighting front, the more these differences evaporated. Men rescued wounded comrades under fire regardless of colour or rank. Medical supplies and food were shared. After the war’s end, many British Officers and N.C.O.s, having been offered the chance of repatriation to the United Kingdom chose instead to first return to Africa with their men before leaving for home.

Men of a West African light battery fording a stream, having broken down their gun in order to carry it.

The following examples will perhaps illustrate the efforts taken to care for and maintain the morale of African gunners The 306th (E.A.) Field Regiment left Amrajan on 6th June 1945 for exercise at Jaipur, Bihar State. On completion of the exercise, it moved to Ranchi, arriving between 17th and 18th June. A holiday was declared on 9th July for the African Other Ranks, who were visited by tribal chiefs from Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika and Nyasaland. In the evening, films were shown in Swahili. On 23rd July, reinforcements arrived from the 302nd (E.A.) Field Regiment, which had recently been declared as a holding unit. In November, all British and African Other Ranks due for release from service and who lived in Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland and Tanganyika were inoculated against Yellow Fever. Three hundred and thirty African gunners visited the Rehabilitation Centre at Divisional H.Q. on 29th December.[1] West African gunners received visits from their tribal leaders. For instance, on 28th October 1944, the Emir of Katsina visited the 251st H.A.A. Battery, W.A.A. at Kumbhirgram, Assam, and inspected African gunners from northern Nigeria.[2] The issue of campaign medals – the 1939-1945 Star and the Burma Star – to the 1st (W.A.) H.A.A. Regiment in July 1945 was well received and it was noted that the African personnel of the Regiment felt especially proud to receive the ribbons.[3]

It is sometimes said that African soldiers did not receive the same entitlement to leave as their British counterparts. Documentary evidence suggests the contrary, with one exception. Whilst serving in Africa, African soldiers were granted local leave wherever they were serving. In the case of West Africa, soldiers from one country serving in another, say Nigerians in Sierra Leone, were granted leave, most notably embarkation leave prior to departing for overseas duty, back to their country of origin. British Officers, N.C.O.s and Other ranks were granted local leave, leave in the United Kingdom or leave in South Africa. The extreme climate in West Africa took its toll of many British personnel and many were granted recuperative leave in the United Kingdom. Once overseas, specifically in Ceylon and India, it appears that the leave arrangements for British and African personnel were broadly similar. The exception being local leave (i.e. leave granted to visit off-base areas in country). When African soldiers first arrived in India they were not well received by the Indian population. To avert the possibility of civil disturbance, the British authorities decided to confine African soldiers to specially built rest camps. In all other aspects, it appears that African soldiers (at least East African soldiers) were granted home leave (i.e. to their homes in Africa) under similar arrangements to those for British personnel. One of the major constraints to the prompt taking of home leave was the availability of shipping.

A leave party from the 303rd (E.A.) Field Regiment, E.A.A. left Ceylon for Kenya as early as 29th November 1943, consisting of four Officers, one British Warrant Office and 202 African Ranks.[4] A scheme was instituted in early 1945 which granted leave in East Africa to African soldiers who had completed between two years five months and three years’ service outside East Africa. This scheme was similar to those instituted for British servicemen, known as ‘PYTHON’, under which those having served away from the United Kingdom for more than three years four months were granted home leave, available transport (shipping) permitting. On 30th April, arrangements were made for the dispatch of the second African leave party to East Africa (the first appearing to have left at the end of February), with thirty-nine fortunate men being selected from the 302nd (E.A.) Field Regiment. Understandably, this scheme was very popular with the African gunners and a second party left for Calcutta on 2nd May.[5]

Implementation of a similar scheme for West African troops had not been implemented by February 1945 when the 14th (W.A.) A.A. Brigade noted that this was having an effect on the morale of West African gunners, whose complaints were becoming more forceful. The morale of all ranks was tested when the move of the 1st and 2nd (W.A.) H.A.A. Regiments to Calcutta for embarkation was cancelled at the end of August owing to the allotted ship being diverted. Care was taken to explain to West African gunners the reasons for delay. Pamphlets titled “Release and Resettlement for A.O.Rs” were received by the 1st (W.A.) H.A.A. Regiment and their contents explained to the Africans. The demobilisation scheme and plans for the return to West Africa were generally well received. Many British Officers and Other Ranks had voluntarily deferred their repatriation to 1st October in order to accompany the African Other Ranks back to West Africa. Application was made by the 14th Brigade Headquarters to G.H.Q. India for the official suspension of release and repatriation of British personnel in units due to be returned to West Africa. This request was approved and had the effect of improving morale by way of having removed uncertainty and giving official authorisation for what the British personnel themselves preferred. When one regiment and two batteries subsequently moved to Kalyan, near Bombay, for early embarkation, morale of both British and African personnel soared.[6]

Implementing repatriation schemes caused serious manpower problems for the immediate prosecution of the war against Japan and for longer term planning. As a result of complying with the East African leave scheme, it became possible to retain as active within the 11th (E.A.) Infantry Division only two field (303rd and 306th) and one anti-tank (304th) regiment. The retained regiments were brought up to strength by the posting of men who were not due for leave, either from the 59th and 60th Batteries or form reinforcements. The 302nd Regiment became a holding regiment, consisting of the 58th, 59th and 60th Batteries:

- 58th Battery: holding African gunners eligible for East Africa leave until shipping became available

- 59th Battery: composed of British and Africans not due for leave and who were surplus to requirements of the retained regiments

- 60th Battery: composed of European personnel eligible for East Africa leave, in the same way as the 58th Battery was for Africans.[7]

It appears that a similar scheme for West African soldiers may not have been implemented before the war’s end in August 1945. This may be because soldiers from West Africa had not served overseas for a sufficiently long period. By the time the scheme for East African soldiers was implemented, many had served overseas for longer than the roughly two years, six months qualifying period. A number would have served in Madagascar in 1942 and the 21st (E.A.) Infantry Brigade, with elements of what became the 303rd (E.A.) Field Regiment, had been in Ceylon since early 1942. In the event, the gunners of the 14th (W.A.) A.A. Brigade began leaving India in early October 1945.

22 September 2025

[1] War diary 306th (E.A.) Field Regiment, WO 172/9476

[2] War diary 251st HAA Battery RA, Abhilekh Patal NAIDLF00780859

[3] War diary 1st H.A.A. Regiment, W.A.A., WO 172/9588

[4] War diary 303rd (E.A.) Field Regiment, E.A.A., WO 172/4020

[5] Official History; War diary 302nd (E.A.) Field Regiment, E.A.A., WO 172/9473; War diary 303rd (E.A.) Field Regiment, E.A.A., WO 172/9474

[6] War diary 14th (W.A.) A.A. Brigade, WO 172/9578; WO 172/9588

[7] WO 172/9473; WO 172/9474